|

I arrived after midnight and the rain was pouring off the roofs of the wooden huts in continuous streams. It was blowing a gale from the sea as it so often did in these parts, and every now and again the downpour became caught up in the wind and driven horizontally. The camp was blacked out; an air raid warning was in progress.

I eventually found the squadron adjutant, who had been expecting me. He told me to pack off to bed and said he would admit me to the honourable membership of 152nd Nizam of Hyderabad’s own fighter squadron at 9 o’clock the following morning.

The next day was September the first, 1940. The Battle of Britain was at its full height. Mr Churchill, having visited the French Premier shortly before the collapse of France was over and that he expected the Battle of Britain to begin just as soon as Hitler was ready for it. I thought what he had in mind was a land-fought battle on English soil.

Our aerodrome was situated, as the aircraft flies, approximately three miles north-east of Portland Harbour, just behind the hills inland from Weymouth. Our station was in Fighter Command’s 10th group and our airfield was an advanced base and satellite of the Wing H.Q. at Middle Wallop in Wiltshire. The people were typical of those on a fighter station; both pilots and ground-staff differed in outlook and temperament from those in other commands by the very nature of their duties. Nothing is certain on a fighter station. You never know when you are going to take off. The enemy gives no warning. A fighter station near the coast is more vulnerable to quick air attacks than those inland. The tempo and atmosphere on a fighter station is one of suspense. If the weather were clear one could be pretty certain that, at first light, midday or dusk, action would come sometimes and suddenly. It might be in the middle of a game of chess, in the middle of a cup of tea, or just as you were lighting a cigarette, perhaps your last. The telephone, what prosaic little household instrument, would become your absolute master and its monotonous ring would harbinger moments of drama to come. The word “scramble” became the code for emergency take-off at the approach of enemy aircraft, which were known as “bandits”. An unidentified aircraft was known as a “bogey”.

At this time, most unidentified aircraft coming from the south were German and the majority of take-offs were scrambles.

A squadron consisted of twelve operational aircraft and twelve pilots to fly them. These were naturally augmented by spare aircraft and relief pilots and so a fighter squadron would have possibly half as many aircraft again in reserve to make up the full complement in the event of aircraft being shot down or damaged in combat. Pilots were killed, had to go on leave, and had to have stand down periods, so usually the full complement of pilots in a squadron would be the same number again. Usually half of these would be officers and the remainder Warrant Officers or Sergeant pilots.

The squadron was divided into two flights consisting of six aircraft in each, and a flight was commanded by its flight commander who held the rank of Flight Lieutenant. Officer pilots apart from the flight commander would either hold the ranks of Flying Officer or the lowest commissioned rank, Pilot Officer. The commanding officer of the squadron was a squadron leader. It didn’t necessarily follow, however, that the Squadron Leader always led the squadron and a Flight Lieutenant a flight. It just depended who was “on readiness” that is, who was earmarked for duty at the particular time. In the air of course things didn’t necessarily work out at all in the way they should do on paper; and after or, during, a combat the squadron would get spilt up. Flights would get spilt up, individual sections of two or three machines would get spilt up, and each pilot and aircraft would become a fighting unit of its own. Ideally of course the squadron should take-off as a squadron of twelve machines and remain as twelve machines throughout the fighting; they should land as twelve machines, too. Sometimes in the melee of a fight sections of two or three machines would be able to stay together and sometimes even whole flights, but seldom the entire squadron.

It can be seen then that our machines might tend to go in opposite directions, as two aircraft travelling in different directions at sometimes three or four hundred miles an hour very soon became separated for good. There were principles to apply but there could, for the reasons stated, be no hard and fast rules to cover every eventuality because, in practice, each of these was different. There were a number of other factors to contribute to chaos apart from purely enemy tactics and evolutions. They included the unaccountable failures in an aircraft itself. Engine trouble, poor wireless reception, oxygen failure, any of these and other emergencies might necessitate a machine or machines having to leave the formation and thus diminish its effective strength as a fighting unit.

Before lunch I went to report to the squadron adjutant. The “Adj”. as he was affectionately known to all and sundry was a middle-aged man who had seen service as a soldier in the previous war. He was one of the many who, having been a regular soldier , was axed when he was too young to retire, and found sanctuary and companionship in the administrative branch of the R.A.F.

The general discipline and administration of the squadron on the ground was invested in the Adj. And although he gave one the general impression that he never did any work, this was merely because he took such pains to prevent the pilots from being worried by petty restrictions and red tape which could serve no useful purpose. The Adj. Seemed to form a sort of absorbent buffer upon whom all the troubles of the squadron fell. Were sorted out, and resolved one way or another without any fuss. We seldom gave him credit for the job he did.

When I entered his office, he spoke to me as father to son and made certain I had everything I needed. He then took me in to see the C.O. whose office was next door to his. The C.O. told me to go down to dispersal and report to my flight commander. I was to be in A Flight and therefore my flight commander would be Bottle (Flt/Lt D.P.A. Boitel-Gill). It was a good mile from the station office to the dispersal hut so I got into my car and drove down there. I identified myself to Bottle and was told to get kitted up with parachute and “Mae West” from the stores and report back after lunch. I got back into the car and eventually found the parachute store which was tucked away in a remote part of the camp. The corporal in charge of the store fitted me out and made one or two adjustments to the straps before I collected the “Mae West” and microphone from the W/T store. I pushed these with the parachute into the back of the car and went up to the mess for lunch.

|

|

Flt/Lt D.P.A. Boitel - Gill (Bottle)

|

|

After lunch I went down to dispersal again ready for flying. “B” Flight we’re at readiness now and “A” Flight were getting ready to go up to the mess for lunch. It was always like this. Only one flight was allowed up to the mess at the same time unless weather conditions made flying impossible when perhaps the entire squadron might be in the mess at the same time. Before he went. Bottle told me to wait till he got back and said he would then take me up in formation to see how I shaped. I was glad that I was going to fly again at last and only hoped that my flying would satisfy him. I sat around rather self-consciously while “B” Flight settled themselves down on their beds, fully kitted up. Some were smoking, some reading and some even trying to snatch some sleep. A few of the more boisterous ones were doing their best to prevent this by ragging about and generally behaving rather like one used to do at school before the lights went out in the dormitory.

The telephone rang and the orderly, phone in one hand and pencil in the other, kept on saying “Yes – Yes” as he jotted something down on the pad in front of him. People stopped ragging and all faces turned towards the orderly with the telephone. With a final “Yes, Sir”, he replaced the receiver and said “Blue section to patrol Portland- Angels twenty “. This wasn’t a scramble, it was merely a precautionary patrol ordered by Group H.Q , possibly because they had got some sort of idea that a raid might develop in that area. No one knew, but Blue section took their time getting off the ground, walking almost casually over to their aircraft. “B” Flight’s commander was leading Blue Section and with him was one of the Sergeants and P/O “Greeno” as he was known to his flight.

The three aircraft started up and, with Pete (Flt/Lt P.G. St. G. O’Brian) leading, taxied out slowly to take-off position. When they were in their positions, one on either side of the leader, Pete waved his hand fore and aft to indicate that he was ready to start rolling, and this was acknowledged by the other two with a thumbs up signal. The three aircraft moved off, apparently as one machine. The noises of the individual engines gradually became absorbed by one another until the sound from them was that of one vast throbbing and pulsating bit of machinery. They left the ground about half way down the grass airfield and, rocking slightly as they pumped their undercarriages up, continued to fly straight on, climbing slowly. Each machine left a long line of blackish vapour behind it which gradually dispersed as they got further away. Then they turned gently to port, now climbing more steeply, and headed out to sea. I watched them until they disappeared towards the sun and wondered what lay in store for them.

Sometime later “A” Flight returned from mess and Bottle went over and had a word with Chiefy to see if there were an aircraft to spare that I could use. He came back with a rather despondent expression on his face to say that there wasn’t one and I would have to wait until after tea. I decided to go back to my quarters and finish my unpacking, feeling rather redundant. I got into my car again and just as I had turned into the road from the mud lane leading to dispersal I heard a lot of excited voice and a general commotion coming from the hut. Almost at once an engine burst into life, then another and another until nine machines had been started up. I realised that this was a scramble. The nine planes which, with Blue Section, made up the whole squadron were about to take off. Pilots were running fast towards their machines and one or two were already taxi-ing out to their take-off positions as I stopped my car to watch.

There was no call for me that evening. The squadron had returned, that is ten of them. They had joined up with Blue section over Southampton, apparently , whither Blue section had been redirected and come into a large formation of Dornier 17 bombers with an escort of M.E. 109 single engine fighters. From what I could gather from the conversation in the mess afterwards, they had accounted for four of the bombers when they were attacked by the escort from cloud cover. One pilot from “A” Flight was shot down in flames by one of these. Almost simultaneously, another, a sergeant pilot from “B” Flight, went down out of control, plunging straight into the Solent. Bottle told me not to bother about my formation flight with him, but to be on readiness in Red section at dawn the following day. To be at readiness at dawn, one had to be at dispersal by five o’clock.

I was called at four-thirty by batman with a cup of tea. I gulped it down, got up and shaved. I was the first to get to the mess and was quickly served with a good helping of porridge by the W.A.A.F. waitress on duty. Dimmy (P/O I. N. Bayles) was next to come in, with his tunic coat still undone, and combing his hair as he sat down. “Operational already?” he queried, looking at me. I said “Yes”. “Good show”, he replied. The other two, Ferdie (P/O F.H. Holmes) and Cocky (P/O C.S. Cox) came in shortly afterwards and both of them made some sort of sign of recognition before starting their meal. Nothing much was said that was of any consequence during breakfast except possibly an occasional reference to the weather. The weather was always of consequence, for when it was good we flew and when it wasn’t we sometimes didn’t but the reason we didn’t or weren’t likely to. Was because the Germans didn’t either.

As I arrived outside the hut, at dispersal, the merest glimmer of the impending dawn showed itself over to the east. It was too early yet to judge what sort of day it would herald but we could reasonably except another cloudless day. A kind of Indian summer had persisted for the preceding two or three weeks and, although it was officially autumn now, the heat of the previous days hardly gave that impression. “M” for mother was dispersed a long way from the hut and after some difficulty I found it.

|

P/O Roger Hall & P/O Pooch with UM-M P9386 at RAF Warmwell

|

|

The machine was soaked with drew and I laid my parachute on a tarpaulin lying by the tail wheel, before clambering on to the port wing to open up the cockpit hood. The inside of the hood was wet with condensation but otherwise the cockpit itself seemed to be fairly dry and I got inside. I released the adjustable seat down to its furthest ratchet and turned the revolving foot screws on each rudder control column until the rudder bar itself was at its fullest extent. Then I got out of the machine to retrieve my parachute. I placed this in the seat recess and sat on it, at the same time doing up the harness straps. I then plugged my wireless receiving lead, attached to the earphones of my helmet, into its socket on the right side of my seat. I put my helmet on and fastened up my cockpit straps which are known as the “Sutton harness”. These are common to all aircraft and are presumably named after the man who invented them. They are designed to hold the pilot securely in the cockpit and yet are fastened in such a way that he can undo them within seconds. Having assured myself that the harness was properly adjusted, I began to check over the machine itself.

Having checked everything and left my parachute inside the cockpit, I slid the hood forward to keep it dry and made my way back to the hut. Inside the others were wrapped up in blankets and trying to sleep. I settled myself on one of the beds nearest the door and lit a cigarette trying to gain sort of composure. It was shortly before 7 o’clock when the telephone rang. The orderly lifted the receiver and almost at once shouted “Red Section scramble. Base angels ten”. I was up like a shot and out of the door before the others. I had a comparatively long way to go to my machine and I ran hard all the way. My mechanic was already at the starter battery when I got there. I leant on to the trailing edge of the port wing and slid open the cockpit hood, opened the small door underneath and got in. My mechanic was on the wing now and helping me to get into my parachute harness. I fumbled with it , my fingers shaking all the time. The parachute was fixed and the mechanic was holding the two upper straps of the Sutton harness above my shoulders waiting for me to fix the right lower one. Eventually all was set and I grabbed my helmet and put it on. My mechanic had taken up position again at the starter battery and was anxiously awaiting my signal to press the button. I switched the petrol and two magneto switches on and gave the priming pump three injections. I put my thumb up and received acknowledgment from the mechanic who then pressed the button. At the same time I pressed both mine and the propeller started to turn. It fired after a few turns and blue exhaust past the open cockpit. The mechanic leant forward and uncoupled the lead from the starter battery, pulling the wheel chocks away at the same time. Finally he gave the all clear signal and I opened the throttle to taxi towards the take-off point, at the same time making a cursory last minute cockpit check as I went.

Cocky and the sergeant pilot who, with me, made up Red section, were just getting into position as I got there. I turned my machine to the left, using full left rudder and at the same time applying hand brake pressure from the lever on the stick. The machine slewed round nicely and I took up my position on the left side of Cocky. After a thumbs up signal to him to let him know that all was in order, Cocky opened his throttle and we started to move. Keeping an unrelaxing gaze towards his machine the three of us gathered speed rapidly. I saw Cocky’s wheels leave the ground and at once felt my own free them-selves . I eased out a bit to the left as Cocky flying as Red one, retracted his undercarriage and in doing so rocked his machine about a bit. This was almost inevitable for you had to change hands, the left hand from the throttle to the stick and the right hand from the stick to the wheel retracting lever. The small lock lever had to be moved fore and aft with a pumping action until the wheels finally locked themselves with a click into the wing recesses. The red light then appeared on the dashboard which meant “Wheels up”. This operation, although tedious to describe , took really very little time in practice but it always involved rather a lot of rocking about in the air.

I was Red three and the sergeant pilot was Red two in the formation. Red one led us into a fairly steep spiral climb over the airfield, turning to the left. I was on the inside of the turn and therefore my speed was the slowest , not being much more than 160 m.p.h. We were climbing at a rate of about two thousand feet a minute with quite a lot of throttle. There was an indistinct crackle coming into my ear-phones but nothing coherent. Shortly before we got to ten thousand feet I started to turn on my oxygen supply. When we had reached this altitude we levelled off I heard “Hallo Mandrake – Hello Mandrake- Maida Red one calling are you receiving me ?” At once in reply came “Hallo Red one –Red-one – receiving you loud and clear – what are your angels”?- “Hallo Mandrake- Maida Red one answering- Angels ten – over”. Hallo Red one, there is one bandit over Chalkpit same angels, Victor 130 degrees – buster”. Hallo Mandrake, your message received and understood, listening out”. Looking at my code card for the day I identified “Chalkpit” as being Southampton and we seemed to be almost half-way there. The code word “Buster” urged one to hurry.

“Hallo Red Section – Red one calling – Line astern – line astern” I moved out to the left while Red two slid in behind and underneath Red one, and then I came behind and underneath Red two. In order to avoid being upset by a machine’s slipstream when flying in line astern it is necessary to keep below the machine in front. The view one got from this position was of the underside of your leaders fuselage and tail through the upper half of your windscreen and the fore part of you hood. We were now travelling at about three hundred miles an hour with almost full throttle, but without having sighted the bandit. It was quite light now, and to the south-east the sky was clear. The sun, recently risen, was not far above the land to our port front. Below, the ground was darker and there were patches of whitish lying in some of the valleys. Occasionally there was the reflection of the sun from a window or from the top of a greenhouse or something. The air was calm and there were hardly any bumps. Everything seemed to be going smoothly and I had become more composed. I wondered how I would feel when, and if, we were to find the bandit.

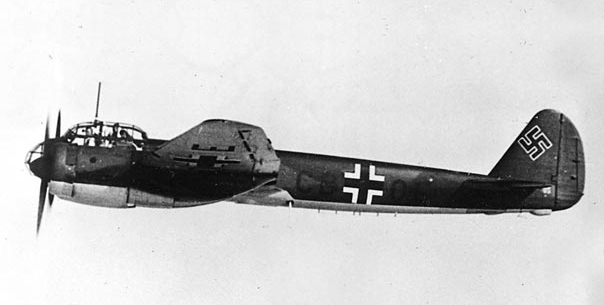

I didn’t have to wait long, for over the radio came “Hallo Mandrake, Hallo Mandrake – Red one calling – Tally-Ho – Tally-Ho “ This latter was the code employed for announcing that a bandit was sighted. Almost at once the reply “Hallo Maida Red one, Hallo Maida Red one – Mandrake answering – good show and the best of luck – Mandrake listening – out” This acknowledgment was merely a background to my thinking, for Red one’s tally ho had imposed a completely new sensation on me, one which I had never before experienced. I find it difficult to describe. At one and the same time I felt both fear and elation, the one attempting to crush me, the other trying to raise me to inexpressible heights. I looked about me for the bandit which Cocky had spotted, but could see nothing. “Loosen up the formation Red section- break right after attack,” came through my ear-phones. I adjusted my reflector gun sight and turned the safety catch of my gun button “Fire”. We had loosened up the formation quite considerably now and there was a distance of about twenty yards or more between the machines to allow plenty of freedom of action and manoeuvre. Now I saw it! It was a little below us off our starboard quarter. It seemed somehow quite incongruous here above the English countryside. It was black and unfamiliar, unfamiliar to me for I had never seen a German aircraft before. It was a Junkers 88 twin- engined bomber. It looked identical to the silhouettes of it on the posters and in aircraft recognition books. It had straight – sided black crosses on the ends of each wing and these were immediately conspicuous because they were bordered with white lines.

|

It was twisting and turning as we were coming down to attack it. It had seen us, there was no doubt of that, for from behind each of its engine nacelles issued a long black stream of oily vapour betraying the fact that it was travelling at full throttle. We ourselves were travelling at little less than three hundred and eighty m.p.h. and were coming in behind it after a shallow diving turn to starboard.

In front of me Cocky and Red two, some distance behind him, were holding their machines fairly steady and I, some way behind Red two, kept my nachine in much the same state. I was impatient to see Cocky open fire but still nothing happened. I was seized with a sadistic sort of curiosity to see what the result of our fire was going to be. I had never seen a aircraft crash or explode or break up in the air and the prospect of it now somehow filled me with a curiosity which, if it did nothing else, served in some measure to dispel my own fear of being shot down by the German rear gunner. The Junkers 88 was keeping a steady course now, presumably to give its rear gunner a chance. The chance seemed to have gone though, for as Cocky broke off his attack and pulled his machine sharply up to the right the port engine of the Junkers 88 was alight. Flames were coming from it and, behind these, long streams of thick black smoke poured. Red two was now attacking the machine’s starboard engine, or so I presumed; it seemed the obvious thing to do, but then, in the air, at times nothing seems very obvious nor are events always what you might expect.

The Junkers 88 exploded. Red two may have been attacking the starboard engine for all I know, but I didn’t know and nobody did or ever would, for the exploding aircraft engulfed Red two, absorbed it, became integrated with it, and the intermingled mass of flaming wreckage fell into the sea and nothing was recovered. I was able to pull away to port as a few fragments from the bomber hit the under surface of my main plane without inflicting any damage. I pulled my machine hard up to starboard to rejoin Cocky. Momentarily I felt all fear disperse and give place to a sort of maniacal hatred which was unnatural . It was hatred of an ungovernable anger. I can’t adequately describe it but I felt certain that if I were called upon to engage the enemy again while this feeling persisted, I should find it difficult to control myself and I should have no heed for my own safety and give no quarter to anyone.

“Hallo Mandrake – Hallo Mandrake” Cocky called up. “Maida Red one calling. Bandit destroyed – Red two lost also – over”. That’s all he said. “Hallo Maida Red one – Hallo Maida Red one – Mandrake answering, your message received – understand bandit destroyed – good show – Pancake – Pancake – Mandrake to Maida Red one, over”.

We were ready to attack. We were now in the battle area and three-quarters of an hour had elapsed since we had taken off. The two bomber formations furthest from us were already being attacked by a considerable number of our fighters. Spitfires Hurricanes appeared to be in equal numbers at the time. Some of the German machines were already falling out of their hitherto ordered ranks and floundering towards earth. There was a little ack-ack fire coming up from somewhere on the ground although its paucity seemed pathetic and its effect was little more than that of a defiant gesture.

We approached the westernmost bomber formation from the front port quarter, but we were some ten thousand feet higher than they were and we hadn't started to dive yet. Immediately above the bombers were some twin-engined fighters, ME 110s. Maida Leader let the formation get a little in front of us then he gave the order "Going down now Maida aircraft," turning his machine upside-down as he gave it. The whole of "A" Flight, one after the other, peeled off after him, upside-down at first and then into a vertical dive.

When they had gone "B" Flight followed suit. Ferdie and turned over with a hard leftward pressure to the stick to bring the starboard wing up to right angles to the horizon, and some application to the port or bottom rudder pedal to keep the nose from rising. Keeping the controls like this, the starboard wing fell over until it was parallel to the horizon again, but upside-down. Pulling the stick back from this position the nose of my machine fell towards the ground and followed White one in front, now going vertically down on to the bombers almost directly below us. Our speed started to build up immediately. It went from three hundred miles per hour to four or more .... Red Section had reached the formation and had formed into a loosened echelon to starboard as they attacked. They were coming straight down on top of the bombers, having gone slap through the protective ME 110 fighter screen, ignoring them completely.

Now it was our turn. With one eye on our own machines I slipped out slightly to the right of Ferdie and placed the red dot of my sight firmly in front and in line with the starboard engine of a Dornier vertically below me and about three hundred yards off. I felt apprehensive lest I should collide with our own machines in the melee that was to ensue. I seemed to see one move ahead what the positions of our machines would be, and where I should be in relation to them if I wasn't careful. I pressed my trigger and through my inch thick windscreen I saw the tracers spirallign away hitting free air in front of the bomber's engine. I was allowing too much deflection. I must correct. I pushed the stick further forward. My machine was past the vertical and I was feeling the effect of the negative gravity trying to throw me out of the machine, forcing my body up into the perspex hood of the cockpit. My Sutton harness was biting into my shoulders and blood was forcing its way to my head, turning everything red. My tracers were hitting the bomber's engine and bits of metal were beginning to fly off it. I was getting too close to it, much too close. I knew I must pull away but I seemed hypnotised and went still closer .... I pulled away just in time to miss hitting the Dornier's starboard wing tip. I turned my machine to the right on ailerons and heaved back on the stick, inflicting a terrific amount of gravity on to the machine. I was pressed down into the cockpit again and a black veil came over my eyes and I could see nothing.

|

I eased the stick a little to regain my vision and to look for Ferdie. I saw a machine, a single Spitfire, climbing up after a dive about five hundred yards in front of me and flew after it for all I was worth. I ... soon caught up with it -- in fact I overshot it. It was Ferdie all right. I could see the "C" Charlie alongside our squadron letters on his fuselage. I pulled out to one side and back again hurling my machine at the air without any finesse, just to absorb some speed so that Ferdie could catch up with me. "C" Charlie went past me and I thrust my throttle forward lest I should lose him. i got in behind him again and called him up to tell him so. He said: "Keep an eye out behind and don't stop weaving." I acknowledged his message and started to fall back a bit to get some room. Ferdie had turned out to the flank of the enemy formation and had taken a wide sweeping orbit to port, climbing fast as he did so. I threw my aircraft first on to its port wing-tip to pull it round, then fully over to the other tip for another steep turn, and round again and again, blacking out on each turn. We were vulnerable on the climb, intensely so, for we were so slow.

I saw them coming quite suddenly on a left turn; red tracers coming towards us from the centre of a large black twin-engined ME 110 which wasn't quite far enough in the sun from us to be totally obscured, though I had to squint to identify it. I shouted to Ferdie but he had already seen the tracers flash past him and had discontinued his port climbing turn and had started to turn over on his back and to dive. I followed, doing the same thing, but the ME 110 must have done so too for the tracers were still following us. We dived for about a thousand feet, I should think, and I kept wondering why my machine had not been hit.

Ferdie started to ease his dive a bit. I watched him turn his machine on to its side and stay there for a second, then its nose came up, still on its side, and the whole aircraft seemed to come round in a barrel-roll as if clinging to the inside of some revolving drum. I tried to imitate this manouevre but I didn't know how to, so I just thrust open the throttle and aimed my machine in Ferdie's direction and eventually caught him up.

The ME 110 had gone off somewhere. I got up to Ferdie and slid once more under the doubtful protection of his tail and told him I was there. I continued to weave like a pilot inspired, but my inspiration was the result of pure terror and nothing more.

All the time we were moving towards the bombers; but we moved indirectly by turns, and that was the only way we could move with any degree of immunity now. Four Spitfires flashed past in front of us .... There was a lot of talking going on on the ether and we seemed to be on the same frequency as a lot of other squadrons. "Hallo Firefly Yellow Section -- 110 behind you" -- "Hallo Cushing Control -- Knockout Red leader returning to base to refuel." "Close up Knockout "N" for Nellie and watch for those 109s on your left" -- "All right Landsdown Squadron -- control answering -- your message received -- many more bandits coming from the east -- over" -- "Talker White two where the bloody hell are you?" .... "I don't know Blue one but there are some bastards up there on the left -- nine o' clock above" -- Even the Germans came in intermittently: "Achtung, Achtung -- drei Spitfeuer unter, unter Achtung, Spitfeuer, Spitfeuer." .... "Yes I can see Rimmer leader -- Red two answering -- glycol leak I think -- he's getting out -- yes he's baled out he's o.k."

And so it went on incessantly, disjointed bits of conversation coming from different units all revealing some private little episode in the great battle ....

Two 109s were coming up behind the four Spitfires and instinctively I found myself thrusting forward my two-way radio switch to the transmitting position and calling out "Look out those four Spitfires -- 109s behind you -- look out." .... The two 109s had now settled themselves on the tail of the rear Spitfire and were pumping cannon shells into it. We were some way off but Ferdie too saw them and changed direction to starboard, opening up his throttle as we closed. The fourth Spitfire, or "tail end Charlie", had broken away, black smoke pouring from its engine, and the third in line came under fire now from the same 109. We approached the two 109s from above their starboard rear quarter and, taking a long deflection shot from what must have been still out of range, Ferdie opened fire on the leader. The 109 didn't see us for he still continued to fire at number three until it too started to trail Glycol from its radiator and turned over on its back breaking away from the remaining two .... At last number one turned steeply to port, with the two 109s still hanging on to their tails now firing at number two. They were presenting a relatively stationary target to us now for we were directly behind them. Ferdie's bullets were hitting the second 109 now and pieces of its tail unit were coming away and floating past underneath us. The 109 jinked to starboard. The leading Spitfire followed by its number two had now turned full circle in a very tight turn and as yet it didn't seem that either of them had been hit. The 109 leader was vainly trying to keep into the same turn but couldn't hold it tight enough so I think his bullets were skidding past the starboard of the Spitfires. The rear 109s tail unit disintegrated under Ferdie's fire and a large chunk of it slithered across the top surface of my starboard wing, denting the panels but making no noise. I put my hand up to my face for a second.

The fuselage of the 109 fell away below us and we came into the leader. I hadn't fired at it yet but now I slipped out to port of Ferdie as the leader turned right steeply and over on to its back to show its duck egg blue belly to us. I came up almost to line abreast of Ferdie ... and fired at the under surface of the German machine, turning upside-down with it. The earth was now above my perspex hood and I was trying to keep my sights on the 109 in this attitude, pushing my stick forward to do so. Pieces of refuse rose up from the floor of my machine and the engine spluttered and coughed as the carburetor became temporarily starved of fuel. My propeller idled helplessly for a second and my harness straps bit into my shoulders again. Flames leapt from the engine of the 109 but at the same time there was a loud bang from somewhere behind me and I heard "Look out Roger" as a large hole appeared near by starboard wing-tip throwing up the matt-green metal into a ragged rent to show the naked aluminum beneath.

I broke from the 109 and turned steeply to starboard throwing the stick over to the right and then pulling it back into me and blacking out at once. Easing out I saw three 110s go past my tail in "V" formation but they made no attempt to follow me round. "Hallo Roger -- Are you O.K.?" I heard Ferdie calling. "I think so -- where are you?" I called back.

"I'm on your tail -- keep turning" came Ferdie's reply. Thank God, I thought. Ferdie and I seemed to be alone in the sky .... Ferdie came up in "V" on my portside telling me at the same time that he thought we had better try to find the rest of the squadron.

....Ferdie set course to the north where we could see in the distance the main body of aircraft. London with its barrage balloons floating unconcernedly, like a flock of grazing sheep, ten thousand feet above it, was no feeling the full impact of the enemy bombers. Those that had got through -- and the majority of them had -- were letting their bombs go ....

....I wondered what the people were like who were fighting the Battle of Britain just as surely as we were doing but in less spectacular fashion. I thought of the air raid wardens shepherding their flocks to the air raid trenches without a thought of their own safety; the Auxiliary Firemen and the regular fire brigades who were clambering about the newly settled rubble strewn with white-hot and flaming firders and charred wood shiny black with heat, to pull out the victims buried beneath; the nurses ... in their scarlet cloaks and immaculate white caps and cuffs, who were also clambering about the shambles to administer first aid to the wounded and give morphine to the badly hurt .... Not least I thought of the priests and clergy who would also be there, not only to administer the final rites to the dying but to provide an inspiration to those who had lost faith or through shock seemed temporarily lost ....

|

“B” Flight resting in the dispersal hut

|

|

I felt humble when I thought of what was going on down there on the ground. We weren't the only people fighting the Battle of Britain. There were the ordinary people ... all going about their jobs quietly yet heroically and without any fuss or complaint .....

We were now in the battle area once again and the fighting had increased its tempo. The British fighters were becoming more audacious, had abandoned any restraint that they might have had at the outset, and were allowing the bombers no respite at all. If they weren't able to prevent them from reaching their target they were trying desperately to prevent them from getting back to their bases in Northern France. The air was full of machines, the fighters, British and German, performing the most fantastic and incredibly beautiful evolutions. Dark oily brown streams of smoke and fire hung in the sky from each floundering aircraft, friend or foe, as it plunged to its own funeral pyre miles below on the English countryside. The sky, high up aloft, was an integrated medley of white tracery, delicately woven and interwoven by the fighters as they searched for their opponents. White puffs of ack-ack fire hung limply in mid-air and parachute canopies drifted slowly towards the ground.

....Beneath us at about sixteen thousand feet, while we were at twenty-three, there were four Dorniers themselves still going north and I presumed, for that reason, they hadn't yet dropped their bombs. Ferdie had seen them and was making for them. Three Hurricanes in line astern were delivering a head-on attack in a slightly echeloned formation. It was an inspiring sight, but the Dorniers appeared unshaken as the Hurricanes flew towards them firing all the time. Then the one on the port flank turned sharply to the left, jettisoning its bomb load as it went. The leading Hurricane got on its tail and I saw a sheet of flame spring out from somewhere near its centre section and billow back over the top surface of it s wing, increasing in size until it had enveloped the entire machine except the extreme tips of its two wings. I didn't look at it anymore.

We were now approaching the remaining three Dorniers and we came up directly behind them in line astern .... I slid outside Ferdie and settled my sight on [a] Dornier's starboard engine nacelle .... The Dornier's saw us coming all right and their rear-gunners were opening fire on us, tracer bullets coming perilously close to our machines. I jinked out to port in a lightning steep turn and then came back to my original position and fired immediately at the gunner and not the engine. The tracers stopped coming from that Dornier. I cnaged my aim to the port engine and fired again, one longish burst and my "De-Wilde" ammunition ran up the trailing edge of the Dornier's port wing in little dancing sparks of fire until they reached the engine. The engine exploded and the machine lurched violently for a second, as if a ton weight had landed on the wing and then fallen off again for, as soon as the port wing had dropped it picked up again and the bomber still kept formation .... The engine was now totally obscured by thick black smoke which was being swept back on to my windscreen. i was too close to the bomber now to do anything but break off my attack and pull away. I didn't see what had happened to the Dornier that Ferdie had attacked and what's more I could no longer see Ferdie.

|

I broke off in a steep climbing turn to port scanning the sky for a single Spitfire -- "C" Charlie. There were lots of lone Spitfires, there were lots of lone Hurricanes and there were lots of lone bombers but it was impossible now and I thought improvident to attempt to find Ferdie in all this melee. I began to get concerned about my petrol reserves as we had been in the air almost an hour and a half now and it was a long way back home.

.... I began to make some hasty calculations concerning speed, time and distance and decided that if I set course for base now and traveled fairly slowly I could make it .... I called up Ferdie, thinking, not very hopefully, that he might hear me, and told him what I was doing. Surprisingly he came back on the air at once in reply and said that he was also returning to base ....

|

“No- one has written more vividly about air combat and the Battle of Britain specifically.... one is in the cockpit with him” SUNDAY TIMES

|

|

|